As a special bonus, all subscribers enjoy complimentary access to this issue of UNBOXED!

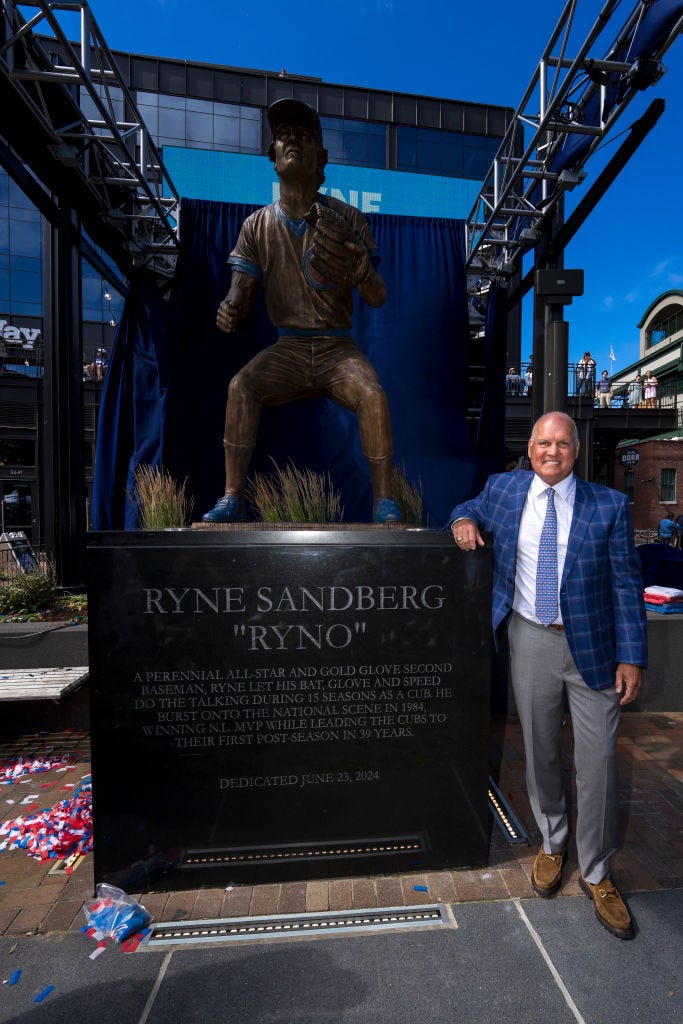

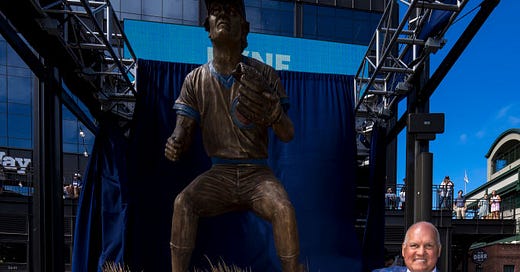

It is fitting that the statue honoring Ryne Sandberg shows him in a ready position at second base. Ryno was steady, focused, graceful, and determined. The pose contradicts the stereotypes often assigned to players who are quiet and introspective like Sandberg. Quiet athletes are frequently labeled as lazy, indifferent, or lacking in passion. Until their numbers say otherwise.

Maybe I am projecting, but I could relate. In my early days of professional baseball, and even leading up to the 1991 draft, I heard some of those same assumptions about being calm and even-keeled. Back then, I could even find them in writing. That was part of why I held a grudge against the great Peter Gammons until I met him. He had written a 1991 draft preview with a one-liner for each potential first-round pick. The line that stuck with me was something like, “Some wonder if he wants to play.”

At 20 years old, I felt misunderstood and offended, partly because I was still inexperienced in the media world. I had not yet learned how to navigate an environment where someone could form a personal judgment of me without ever speaking to me or, in some cases, even seeing me play. I went so far as to prepare a mental defense, just in case a reporter or scout questioned my commitment. I ended up using this defense in an interview with the New York Times when the reporter cited a convoluted hearsay chain to suggest I lacked dedication. According to the reporter, his son’s friend, who played on the opposing team, claimed he had a brief conversation with one of my teammates who supposedly said that “he only shows up when he wants to,” regarding my absence from that one game. The most puzzling part? This alleged exchange dated back to my early teens, many years before this particular New York Times interview even took place.

So I was intrigued by Sandberg and his quiet greatness.

Ryne Sandberg let his bat, glove, legs, and his Hall of Fame career do the talking. But it was not always that way.

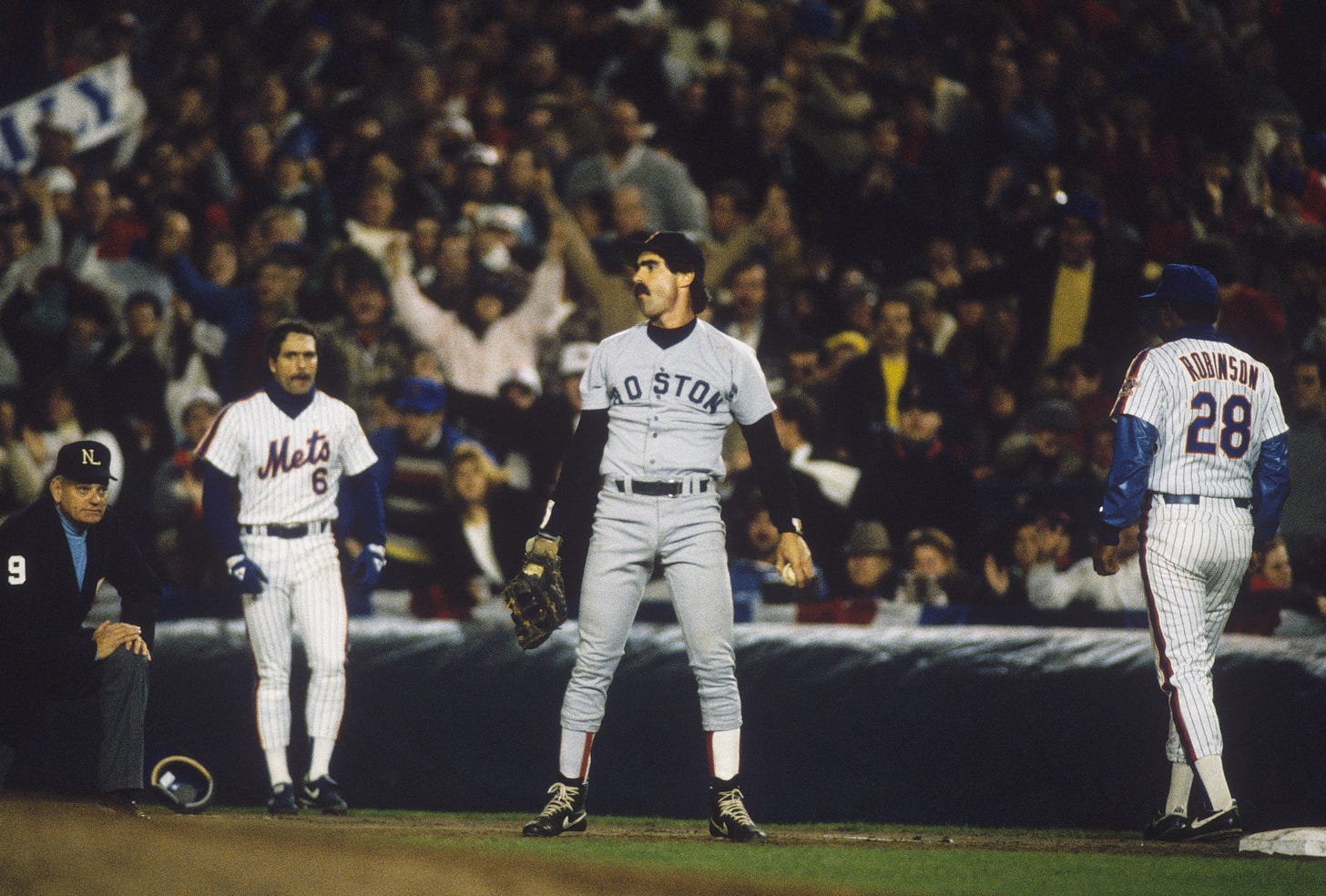

I wrote an essay for the book accompanying the baseball exhibit “Chasing Dreams: Baseball and Becoming American” at The Weitzman National Museum of American Jewish History Museum in Philadelphia. In it, I traced the degrees of separation between Jackie Robinson and me through the game of baseball. Two degrees were Bill Buckner and Ryne Sandberg.

To write the essay, I interviewed both men. Buckner shared a memorable story about Dick Allen. When he first played with Allen, Buckner was known for his intensity and frequent outbursts after making an out. After one particularly loud tirade, Allen approached Buckner and asked, “What’s the matter? You don’t think you’ll ever get a hit?” That moment stuck with Buckner and helped him learn to channel his intensity into preparation and purpose.

After his trade from Philadelphia to the Cubs, Sandberg paid close attention to Buckner’s precise work ethic. By then, Sandberg had already grown weary of the criticism about his supposed nonchalant demeanor. He carried with him a memory from the minor leagues where he once tried to be outwardly expressive at the request of his minor league manager, Bill Dancy.

“You need to break a helmet once in a while,” Dancy told him.

So, in an attempt to follow instructions, he smashed his helmet after a particularly frustrating at-bat.

Then, in classic Sandberg fashion, he reflected to me, “I thought to myself: Now what? I don’t have a helmet anymore,” and continued, “What did that prove? Well, it proved I could break a helmet.”

Eventually, the true inner Sandberg prevailed. The one that could quietly dismantle opponents without breaking a sweat. The Sandberg who would win an MVP, earn multiple All-Star selections, and eventually walk into Cooperstown. He said very little, but he carried a big stick all the way.

And, he cared deeply. Enough to experiment, to try being different. He recognized the perception that he did not care, but he ultimately returned to playing the game he loved in the only way he knew.

After all, baseball is a team sport. You need all types of players to keep the ship sailing. If Ryno needed unfiltered truth, there was Mark Grace or Shawon Dunston. If he needed someone to finish a fight, he had Rick Sutcliffe or Jody Davis. But if the team needed a steady hand and a quiet, burning belief, Sandberg was the guy to shine in that role.

That quiet confidence became important to me and my career. When Sandberg broke his hand in spring training of 1993, he came to Daytona Beach, Florida on a rehab assignment. I happened to be in my second full season in the minor leagues there.

He was with us for just a few games, and he barely said a word. I remember his big-league jersey, with his name on the back, glistening in the Florida sun, especially compared to our nameless Daytona Cubs uniforms.

But we all watched him. His work ethic, his preparation. We had a major leaguer in our midst, and everything he did was a lesson. What did he eat before a game? Did he hit off of a tee? Did he take extra ground balls before the game? What did he do in the on-deck circle?

To impressionable A-ball players, this was a free education.

But for me, I focused on something more personal. He was calm, intentional. He looked casual on the outside, but he cared. He was competitive, and he led by example, without having to say anything. No speeches, just a line or two of advice in private that carried more weight than a locker room address.

It gave me the freedom to challenge the labels I had been given, realizing that maybe those who assign labels are actually the lazy ones. Too impatient to take the time to really understand and get to know a player. Sure, it is important to listen and accept feedback, but I have always found it a stretch to accuse someone of not caring. Especially if the accusation is based solely on volume.

The following year, I made the 40-man MLB roster for spring training in Arizona. Fortunately, the Cubs put my locker next to Sandberg’s. I had a front-row seat to his routine. And long before I fully understood his work ethic, I took comfort in knowing you can be true to yourself and still add value to your team, and to your own performance.

Over 162 games, it turns out, it does matter that you do not smash 162 helmets at every inevitable setback. You will eventually get a hit or win a game, not just because the Earth keeps spinning, but because you have been consistent, prepared, and believed in yourself.

Labels do not account for time. They are snapshots, often tinged with bias. They do not require investment in someone’s growth, nor do they allow space for evolution. They are static, but dangerously sticky.

One label that my Triple-A manager tried to pin on me was about a lack of toughness. Even making the big leagues did not change his mind, but at least then I had a platform to push back. When a reporter asked me about the lack of toughness comment attributed to my manager, I responded, “No one has the power to define who is tough. We will never know who is truly tough until the smoke clears, and we see who is still standing.”

And I was still standing.

Ryne Sandberg endured. He produced. And he is beloved. He did it his way, even after trying to smash a helmet or two to quiet his early critics.

I was honored to be his teammate. And the greatest gift he gave me had nothing to do with hitting a slider, or surviving a nightmare (for me) pitcher like Stan Belinda. His gift was silent, unboxed, and completely free: Be yourself, and trust your passion for what you love, no matter how you express it.

Then go out and keep that front side closed.

And just like the statue of Ryno outside of Wrigley Field, those gifts will last a lifetime.

What a beautiful tribute to a teammate and a wonderful ballplayer. I hope you were able to pay that gift forward.